On Camaraderie and Constancy

"We've never been more connected, but never felt more alone."

Pretty sunny outlook to start a piece with, eh?

I don't recall where I first read this quote, but it's a problem I feel has been getting worse as technology has become more enmeshed in our lives. Communication has become more impersonal; we've gone from talking in person, to phone calls, to texting, and I only assume what comes next will be some pseudo-sign-language where we communicate solely through gifs and emojis.

With social media and other modern forms of communication we've increased the quantity of interactions in our lives, but decreased the depth and quality of them. An article I came across in The Guardian a few years ago claimed that about 9% of the population in the UK said that they don't have a single close friend. One in five people said that they "never or rarely felt loved" in the two weeks prior to the survey.

A more recent study found that 22% of millenials stated they have no close friends, and one-third of them reported "feeling lonely often or always". While this study by Cigna from 2018 found that 46% of participants sometimes or always feel alone, and 47% feel left out.

So what gives? We've got all this amazing technology that seems to solve all our problems, with more and more popping up every day. Why is there still this glaring problem that hasn't been solved, and only appears to be getting worse?

To my mind this is one of many problems that arises as a result of primitive human biology clashing with the modern world. I wrote about some of the others in my piece on stress, and addressed many of the health issues in the interviews I conducted for The Deskbound Podcast. I also touched on it briefly in the piece I wrote on my return to civilian life, but I feel it deserves a closer look.

This is an issue that I think in some ways affects digital nomads more than most due to the short-term nature of friendships and relationships that it cultivates. Yet in some ways it's less of an issue, as nomads tend to live in places where they have more control over their time and are more prone to have spontaneous run-ins with friends at the cafes they work from, or more regular interactions if they opt for a coworking space.

Regardless, there are (again) pros and cons to both lifestyles, and I think if you analyze the positives of both sides it's not too difficult to weave them together and get a better end result.

So without further ado, let's get into it.

A Wolf Without a Pack

I might be in the minority on this, but I'm of the mind that despite the massive advances in technology and knowledge over the past few millenia, we humans are fairly primitive creatures in many ways. Sure we've achieved a great deal, but we're all standing on the shoulders of giants that came before us who have accomplished so much, and carried humanity so far to get to this point.

Yes, we have a great capacity for learning and expanding our knowledge. Yet if you took someone who would go on to accomplish great things in this life, and at birth swapped them into a hunter-gatherer tribe that lives the way their people did thousands of years ago, I have no doubt that they'd grow into that lifestyle very well. Hell, there's a good chance they'd be much happier than someone living in a first world country!

Humans are adaptable creatures, that goes without saying. But there are a few core pieces that were present for the lion's share of our evolutionary timeline, and have eroded over the past hundred years or so; with that pace being accelerated since the beginning of the technological revolution that we're in the middle of right now.

We humans are adaptable, but we're also very tribal. That shouldn't be news to anyone these days, look to pretty much any online "discussion" to see evidence of that. Watch liberals and conservatives go at it. Or carnivores and vegans. Or pro-life and pro-choice folks, LGBTQ versus bible thumpers, flat earthers against people capable of rational thought...

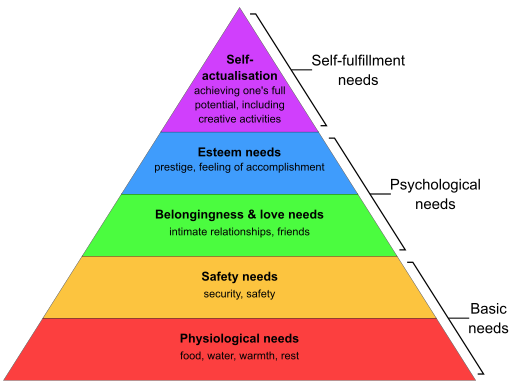

The list goes on and on. One constant of human history is that people seem to want to belong to something larger than themselves. This doesn't HAVE to be an ideological association, where there are clearly defined allies and enemies. People are often content simply having a good group of close friends around them, it gives a certain peace of mind. This shouldn't be too surprising, as "intimate relationships, friends" are the third tier of Maslow's hierarchy of needs, just above "security, safety" and "food, water, warmth, rest":

This inherent need for community and Maslow's hierarchy fit into a larger concept that's been on my mind a lot the past few years.

Threat Buckets and Finite Perseverence

I was introduced to the concept of "threat buckets" in my learning around the effects of stress on chronic pain. The in-depth analysis of that topic is too deep for this piece and better insight is provided in my interviews with Dr. David Hanscom, Cathryn Jakobson Ramin, and Ryan and Missy of Death of the Desk.

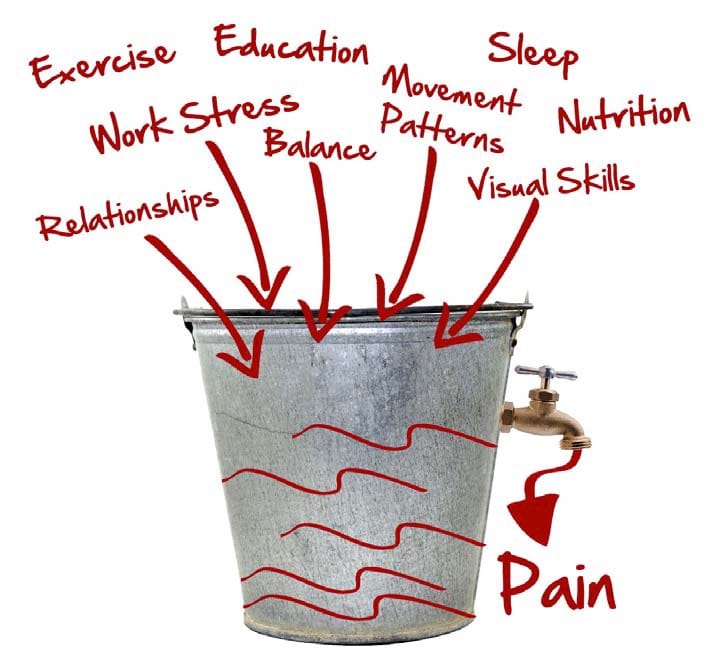

The short version is to think of your capacity for dealing with the different stressors in life as a bucket, and the more stressors you put in the bucket the more it fills up. When it gets to the point of overflowing, you've got some serious problems. You've passed the threshold of your allostatic load(think of that as the maximum stress level you can tolerate for good health) and are beginning to suffer the consequences:

I think that the majority of contributors to filling up the threat bucket come from the first four tiers of Maslow's hierarchy. Most of us have the basic needs on tiers one and two sorted out, though I think that not sufficiently addressing the psychological needs on tiers three and four can cause issues with rest on tier one, and security on tier two.

The reasons these issues manifest are many-fold. As I said before, we traded quality of interactions for quantity which damages tier three of the hierarchy, and even if we accomplish things worthy of prestige to address tier four, we often don't have a close social circle to celebrate that accomplishment with.

This is best summarized by a quote from Christopher McCandless in the book/movie Into the Wild:

Almost everything we can do in this life is better when we can do it with other people. I love playing volleyball, but I enjoyed it more when I had my good group of friends in Colombia to play with every week, to the point that I'm not even playing regularly right now despite there being an active group in my city.

I love cooking a big feast, but who wants to cook elaborate dishes for just themselves to eat? Cooking and sharing a meal with friends is what makes it enjoyable.

I love accomplishing difficult things like running the Tough Mudder or the Medellin Marathon, but doing the Mudder with my brother and close friends back home felt like a much bigger accomplishment, because of the feeling of comradery that we did it together.

Not only that, you also don't want controllable stressors such as these to go unaddressed for too long. As I said before, when the stress bucket overflows it can wreak some serious havoc; not just on your health, but on your tolerance for stress in other areas.

Stress Tolerance and Point of Maximum Growth

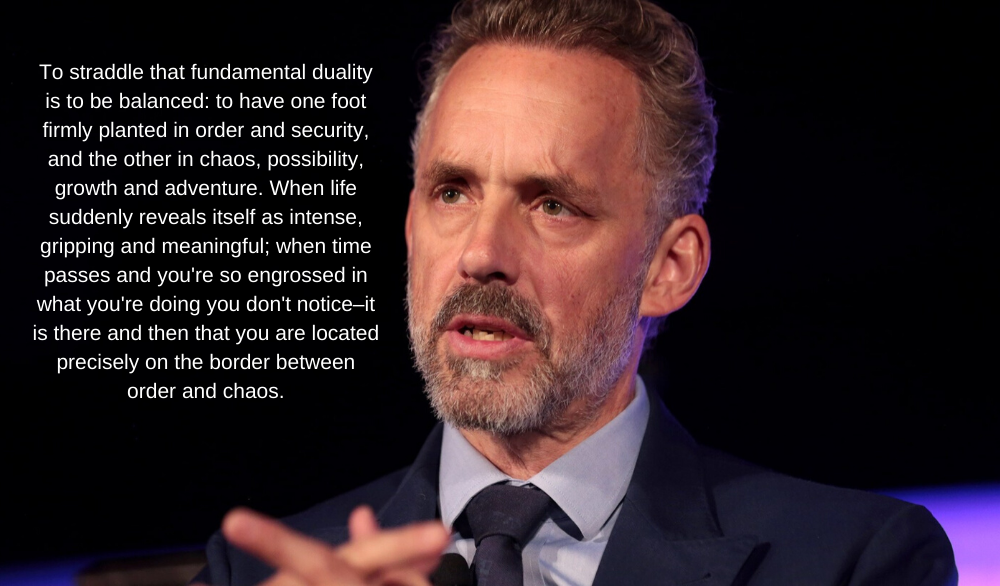

Jordan Peterson often says that the point of maximum growth exists on the border between chaos and order:

This is a point many of us are striving towards. We've been bombarded endlessly with the images of what's possible in this day and age. Thanks to modern technology the amount that one person can accomplish in a lifetime has never been greater, and that creates a lot of stress and pressure to act.

We have more options then ever before of different paths to choose, but thanks to the paradox of choice that leads to more uncertainty and less feeling of satisfaction with the choices we do end up making. The working world that we operate in these days is very different from that of our parents and grandparents.

We're all trying to build the foundation for remarkable careers or businesses on top of the constantly shifting sands of rapid technological change. It's not enough to simply "show up and work hard". You need to bring eleven-tenths of your energy and creativity if you want to do something truly remarkable, and you need to do that consistently for months or years at a time to finally get there.

If you're living and working as a nomad, can you honestly say that you think you can bring as much to your work as you could have if you lived in one stable location, and had a solid group of friends around you?

This is another piece of my reasoning behind returning to civilian life for a while. It's impossible for me to do my best work when I have an uncertain professional future with a modestly successful e-commerce business and a teaching gig where the hours are shrinking rapidly.

I can't, as Naval Ravikant said, "play long-term games with long-term people" when the people I surround myself with are changing every few months; and it certainly doesn't help that most of them are in it for the lifestyle and will do whatever they have to for work to live this way.

Hell, when I'm traveling I can barely do the things I like to unwind after a long stressful day like cooking, or playing sports or games with friends.

Succeeding in the modern world involves dealing with a high level of professional instability. If you're also dealing with a high level of locational instability (digital nomad) and relational instability (lack of close friend group), then you've handicapped yourself before the race has even started.

Closing Thoughts

For me this is another contributing factor behind my reason for moving to Denver. On this next point I can't cite a bunch of evidence behind my reasoning, but I feel it's true nonetheless: I don't think it's feasible to really have the type of close friend group necessary to gain the benefits of this unless you live in a city, or a smaller town that has a tight-knit community. The suburbs are just a shitty compromise between the two.

I spent most of my life living in the suburbs, and as many of my friends know I have a very severe loathing for them now. I bought a house right after turning 24 and lived there for about 4 years, yet I only really knew one or two of my neighbors, and I certainly wouldn't have called them close friends(probably wouldn't have called them friends at all, to be honest).

Sure I could drive to different places to meet my friends, but it just wasn't the same. I learned that from my time living in Medellin and elsewhere, there's a certain joy that comes from living in a tight-knit community where you just run into friends randomly throughout your day. This was even mentioned as a key part in How to Design Our World for Happiness by Jay Walljasper:

The way we design our communities plays a huge role in how we experience our lives. Neighborhoods built without sidewalks, for instance, mean that people walk less and therefore enjoy fewer spontaneous encounters, which is what instills a spirit of community to a place. A neighborly sense of the commons is missing.

Establishing a home base for yourself in a community you know well provides a sense of security (Maslow's hierarchy tier 2) and allows you to develop lasting intimate relationships and friendships (tier 3), both of which put people at ease and allow them to better rest in their off-time (tier 1), and focus on the goal of accomplishing difficult things that make them feel fulfilled and content in life (tiers 4 and 5).

As is often the case, wise people who came before us already knew all of this. Sometimes, to design our ideal future we need only look toward the past:

So ask yourself, do you feel like you're part of a community where you live? Do you have close friends that you see often, or run into randomly? Friends that you know will have your back if shit goes sideways? If not, what are you willing to sacrifice to make that a reality?

I already found my answers, but I think more people should ask those questions.

Brandon